Within a few days after beginning employment with the Louisiana Department of Wildlife and Fisheries in 1977, I was riding a bucking bronco on the banks of Bayou Nachitoches in Avoyelles Parish.

Each wild leap would give me a glimpse of blue sky followed by muddy, rough ground rushing toward my face as the steed pitched and dived.

But this was no rodeo, and this bronco wore Firestone All-Terrains instead of horseshoes.

The ’73 Ford Bronco was grinding along a deeply rutted trail that followed the south bank of Bayou Nachitoches in Grassy Lake Wildlife Management Area. Even referring to it as a trail was giving way too much credit.

I had been told the route would bring me to the Red River and the eastern border of this recently acquired WMA. But doubt filled my mind as the Bronco bounced and rocked along for miles.

After more than three hours, the river came into view, verifying this was, indeed, the right trail. The bad news was that this was the best way out as well as in, meaning I had to turn around and do it all over again if I wanted to see home that night.

This was one of many days spent in the summer of that first year learning my way around country I had not seen before being hired. Not only was I learning the assigned patrol area, but I was also figuring out that if it was this bad during the relatively dry summer months, many of the wood’s “roads” would be far beyond the capabilities of my trusty Bronco come winter. Sure enough, by December only those four-wheel-drive vehicles equipped with the most-aggressive tires, lift kits and winches could get in and out of the woods. And they far exceeded anything the Department provided.

Three-wheeled ATVs were coming into the picture, providing access to places trucks couldn’t go. But the Department was still years away from equipping wildlife agents with ATVs, so we were left behind on that score, as well.

Many local hunters born and raised in the rough, muddy back-country terrain of Avoyelles Parish had a way of getting around all winter long — quietly and without need of winch, mud grip or gasoline. They used horses to travel in the deep woods.

Hunters commonly went about their business on horseback. Of particular interest were the raccoon hunters.

Fur prices were good in the late ’70s and early ’80s, and coon hunting was big business. A large, prime coon hide sold for around $18, and a hunter with good dogs and a reliable horse could harvest eight or 10 coons in a night.

Not a bad night’s work in those days.

Trappers were using horses to run trap lines, as well.

In addition to the coon hunting and trapping, a lot of illegal hunting involved horses.

So it did not take long to realize if any meaningful enforcement was going to be done off the maintained roads, I was going to need a horse. Fortunately, the Department owned a couple.

They were located at the Saline (now Dewey Wills) Wildlife Management Area. I contacted the WMA supervisor with a request to use the horses for a while. He was happy to transfer the horses, trailer and tack to me for as long as needed.

One steed was tall and red, while the other was short. And I don’t know whom the imaginative thinker was naming the pair (probably the agency’s secretary), but they were called “Red” and “Shorty.”

Names aside, they were surprisingly good horses. Red had a beautiful gait, and was perfect for traveling long distances over open country. Shorty was a good woods horse, never banging your knees or rubbing your legs against trees. They were well behaved, reliable and gentle.

I spent a lot of time patrolling Grassy Lake and Pomme de Terre WMAs, looking for illegal campsites, permanent structures such as duck blinds and deer stands, and any other illegal or prohibited activities.

The horseback patrols were very effective. I was able to find numerous illegal campsites and duck blinds, and issued summonses to the offenders using them. One of those camps was accessible only by horse, and the offenders even had a horse corral by the camp for their own horses.

Some might have thought it foolhardy, but I rode the WMAs during open deer season, wearing an orange vest and hat with orange flagging tape on Shorty’s mane, tail and saddle stirrups. I never had a problem, and it was a great way to quietly get to where a shot had been fired and determine whether it was a legal kill.

Checking horseback fur trappers was also made possible.

Admittedly, I limited night patrol. It was simply too hazardous. Over in East Texas, a night rider had been shot and killed by a poacher who shined the horse’s eyes and fired a load of buckshot thinking it was a deer.

And I vividly remember one night when I had to quickly dismount and throw my coat over Red’s eyes while a poacher drove by in a truck, shining a spotlight in our direction.

I like to think the horse patrols were good public relations, as well as effective job performance. After the initial surprise of seeing a game warden on a horse, many hunters would strike up a conversation and ask all sorts of questions. One thing was certain: The horse got more snacks and pats on the shoulder than the rider.

For a time we brought the horses out to the National Hunting and Fishing Day event, and people loved them.

In time, Shorty and Red returned to Dewey Wills, where they were used to address an illegal free-ranging cattle problem on the WMA. The department never acquired any more horses, but did start purchasing more 4X4 trucks and ATVs. For a short time in the late ’80s a few agents used personally owned horses for patrol on rare occasions, but the practice did not last.

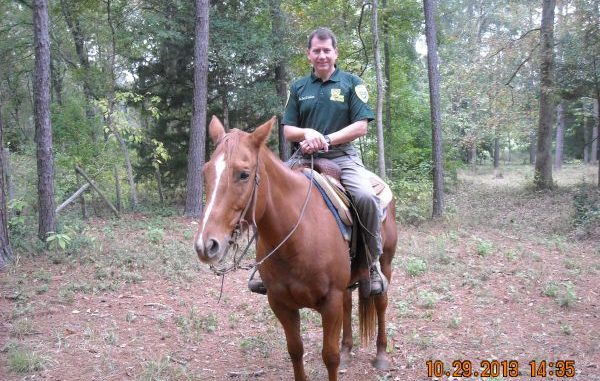

Some of the fish-and-game agencies, particularly in the West, continue utilizing horses even today. The agencies either own the horses or pays a stipend to cover expenses on horses owned by officers and used for work. My good buddy and fellow retired game warden Rick Pallister of Buffalo, Wyo., had a great pair of horses he used to patrol the back country of the Big Horn Mountains in his work district. I always envied him that aspect of the job.

Out West, active-duty wardens continue riding deep into the mountains where only a horse can go. And that is just as it should be, both from a traditional sense and a practical one. After all, a four-wheeler won’t let you know a grizzly is sniffing around camp, but a horse will.