In a state laced with streams, rivers, bayous, lakes and marshes, pretty well anyone who spends time outdoors knows that Louisiana has a lot of gars.

But we have more than just numbers: Louisiana is home to four of the five United States gar species.

Most well-known to fishermen, simply because of its impressive size and ferocious appearance is the alligator gar, a species that can produce fish weighing more than 200 pounds and one found in both fresh and brackish waters.

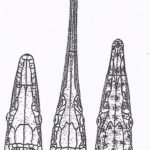

It can be separated from the other three species by its broad, alligator-like (hence its name) snout.

Snout shape as well as coloration are also the key to identifying the other three garfish species.

Certainly the easiest to identify is the longnose gar, Lepisosteus osseus, often called the “needle-nose gar” by fishermen. It is not as common in any one place as the other species, but like the alligator gar it is widely distributed.

The other two species — the shortnose gar (Lepisosteus platostomus) and the spotted gar (Lepisosteus oculatus) — are easier for fishermen to confuse with each other unless they know what to look for, which is snout color rather than snout shape.

The spotted gar, true to its name, has dark spots on top of its snout. Its body color and snout shape are indeed different than the shortnose gar’s, but identification is so simple using the snout’s spots or lack of them that using other features is unnecessary.

Scientific names for garfishes are very descriptive. The word lepisosteus is Greek and means “scale-bone,” which is what they have: scales of bone.

Incidentally, osseus means “of bone” in Latin, platostomus means “broad-mouthed” in Greek, and oculatus means “eyed,” a Latin reference to the round, dark, eye-like spots on tops of their heads.

Of the three species under discussion here, the longnose gar grows the largest and is the most piscivorous (fish-eating). It often reaches more than 5 feet in length, but because much of that is snout and the fact that the fish is more streamlined than other gars, it weighs less per foot than does its other large relative, the alligator gar.

The current longnose gar world record stands at an even 50 pounds, although larger ones have certainly been caught by commercial net fishermen. The world-record alligator gar weighed an impressive 279 pounds.

Although their diet focuses on fish, most of the species eaten are not important game or commercial fish. Studies indicate that in freshwater they feed most heavily on shad, topminnows, shiners, bullhead catfish and small bream.

Like alligator gar, longnose gar range into brackish coastal waters. There they feed heavily on menhaden, croaker and spot. Ninty-eight percent of the diet of longnose gar is fish.

The shortnose gar is the smallest of Louisiana gar species and is the one that recreational fishermen are least likely to encounter. They are silt-tolerant and are most common in large, muddy rivers like the Mississippi, Red and Atchafalaya.

The current world record stands at a whopping 8 pounds, 3 ounces, although most are less than 4 pounds.

It is, of course, a fish predator, but compared to longnose and spotted gar, a much larger percentage of its diet is made up of insects. During cicada (what Southerners call “locusts”) outbreaks, shortnose gar have been recorded to feed almost exclusively on these large insects.

Although shortnose and spotted gar are seldom found in the same habitat at the same time, a food-habits study was done on one such population in an Arkansas river. The most-common foods (by percentage of stomachs it was found in) for spotted gar were fish (74 percent), crawfish (26 percent), aquatic insects (11 percent) and terrestrial insects (9 percent).

The breakdown for shortnose gar was fish (59 percent), aquatic insects (24 percent) and terrestrial insects (35 percent). Additionally, 17 percent of the shortnose gar stomachs contained amphibians (frogs and salamanders).

The last guy in the lineup, the spotted gar, is the one that recreational fishermen end up dealing with most often. This gar is a specialist of clear, still or very slow-moving fresh water, such as that found in Louisiana’s bayous, swamps and lakes. This is the very same habitat so friendly to the freshwater game fish Louisiana sports anglers pursue.

An intensive study of spotted gar was conducted in the Atchafalaya Basin in the late 1990s. The most-commonly eaten foods there were crawfish (48 percent), bream (22 percent), shad (9 percent), crappie (5 percent), bass (4 percent), bowfin or chopique (2 percent), and shiners (1 percent).

A later food-habits study done in the upper Barataria estuary showed that fish were more important in spotted gar diets in the fall than the spring, and were intermediate in winter and summer. Shrimp were more abundant in the summer than fall, and were intermediate in winter and spring. Crawfish were most abundant in the winter, followed by summer and were least important in spring and fall.

Amphibians were more abundant in summer than in fall and winter, and were intermediate in spring. Insects were more abundant in spring than fall and winter and were intermediate in the summer.

The feeding behavior of spotted gar is similar to that of the other two gar species discussed here, in that they are ambush predators and seldom actively chase down their prey. Typically, they float very still in the water until a potential food item nears them, which they then take with a lightning-quick sideways strike.

Spotted gar, in particular, like to float near fallen logs or brush tops or beneath overhanging woody limbs, which may serve to disguise their presence.

All three species, but particularly the spotted gar, become more active and feed more heavily at night.

Spotted gar outfitted with radio transmitters in the Atchafalaya Basin, showed virtually no movement during the day, but actively patrolled their home range at night. Home ranges averaged 17 acres during all times of the year except during spring river floods, when it increased to an average of 663 acres.

Like the alligator gar, all three smaller species are considered to be good food fish, with lean, mild flesh. Gar eggs should not be eaten, however, as they are consistently reported as being toxic to land animals, although not other fishes.